Struggling to Survive.

Life in Africa can be a daily struggle, a relentless challenge for many, but it’s even more difficult and heartbreaking for a child. Imagine growing up without life’s most basic necessities: food, clean water, medicine, shelter, safety, even a bed to call your own. There are no toys to play with, no dolls or footballs, no sweets or simple joys. At best, a child might sleep on a mat made of reeds. Education could be the way out of poverty, a path to hope but with no money for school fees, many children are left behind, waiting for a miracle that may never come. For too many, life is not about living, it’s about surviving.

Growing Up in Uganda. A Daily Struggle Beyond Imagination

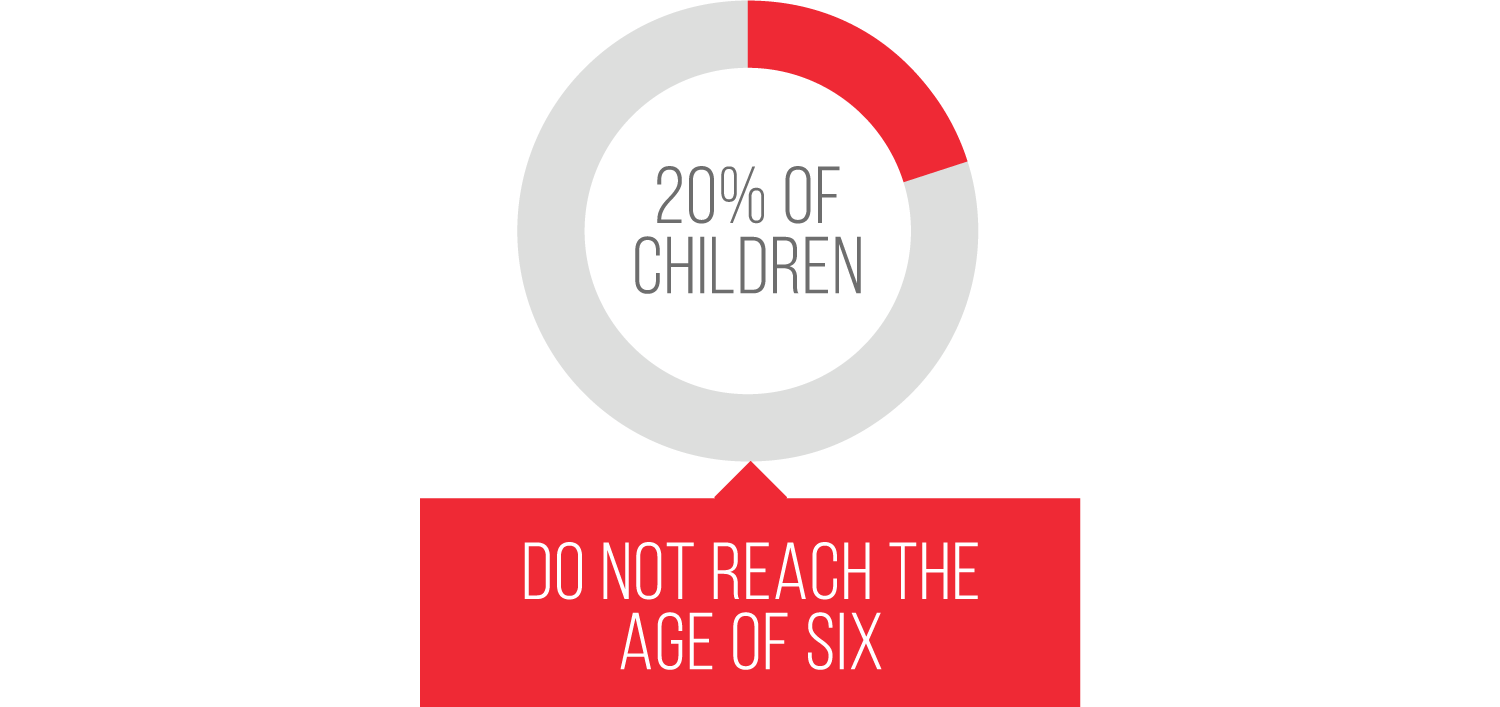

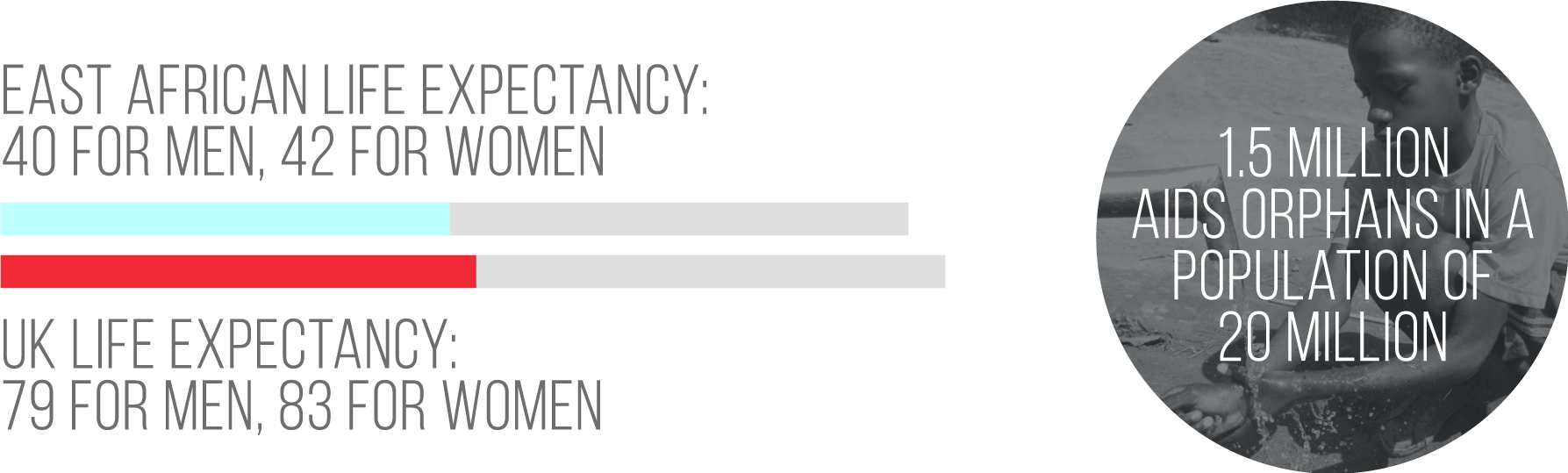

Reaching the age of six is a gift not all children are so fortunate. Many of your friends have already died from preventable causes like malaria, dysentery, and malnutrition. The fact that both your parents are still alive is yet another miracle. In East Africa, the average life expectancy is just 40 years for men and 42 for women. It's rare to see elderly people with gray hair. Malaria remains the leading cause of death, but AIDS follows closely behind. Its impact is visible everywhere offices, villages, schools, and even government institutions bear its mark.

Walk into any school and ask how many children have lost one or both parents, and you'll be shocked by the response. In a country like Uganda, with a population of 20 million, there are an estimated 1.5 million AIDS orphans. Many of these children are forced to fend for themselves on the streets because life at home has become unbearable.

Yes, there is rebel conflict in the north and west of Uganda. Yes, malaria and other illnesses take lives every day. But AIDS is a different kind of war, a silent killer that creeps through communities, robbing them of their future. In fact, some businesses in Kampala no longer allow employees time off for funerals—death has become too common. One of the most stable jobs in the city is working at a funeral home. Sadly, there is never a shortage of customers.

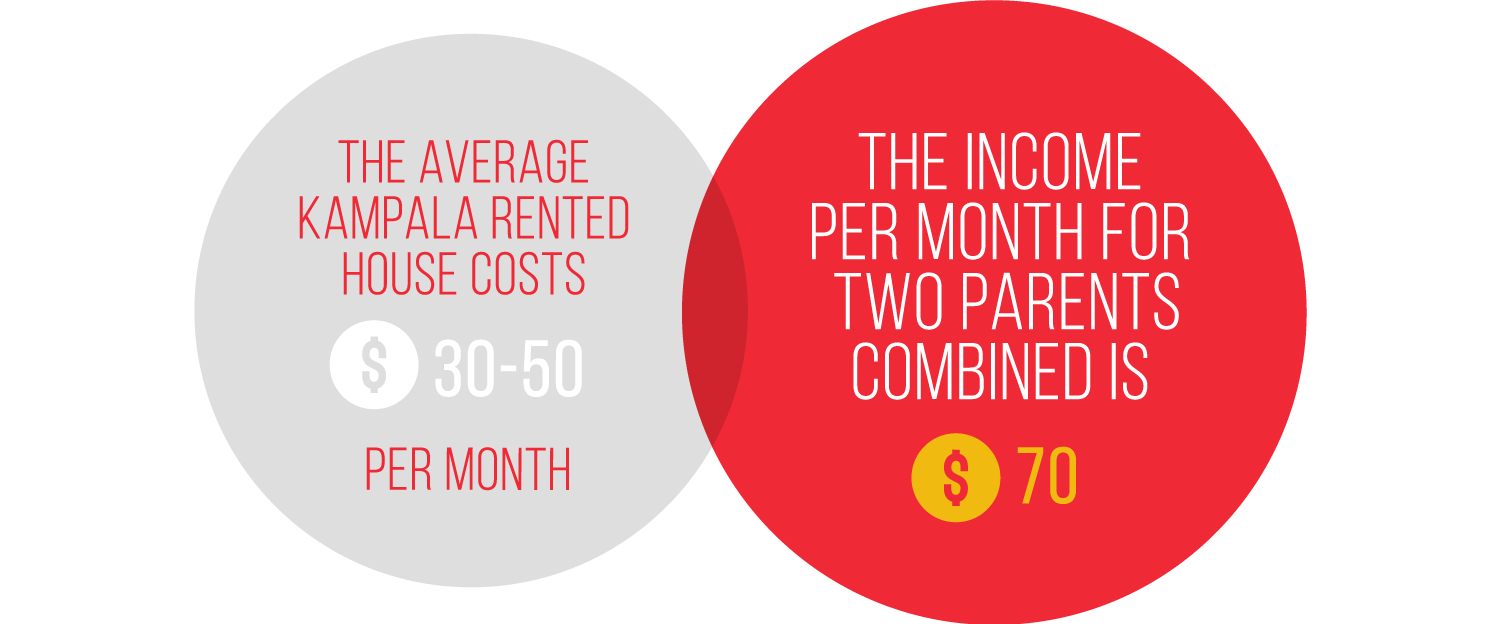

So here you are a child in Africa, living in a small shack made of sun-baked mud bricks, topped with a corrugated tin roof that leaks whenever it rains. The house is tiny, just one room and if you're lucky, two. There’s no kitchen, just a charcoal stove outside. A bag of charcoal costs about $35.71 and, for some, it has to last an entire month. If there's no money, you gather firewood to cook your meals. The bathroom is a shared outhouse down a dirt path, used by many families. Most people bathe using plastic wash tubs, typically twice a day. In a city like Kampala, a home like this rents for $20 to $40 a month, located in slum areas where makeshift houses of mud and cardboard are common.

Your parents' combined monthly income is around $55. Your father works as a night watchman for a wealthy family from 7:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m. Your mother leaves home at 6:30 a.m. to work as a maid or help at the market whatever work is available that day. You’re a 12-year-old girl, and you're home alone. Well, almost. Sometimes your father gets a few hours of sleep, then heads back out, trying to find extra work to earn a few more shillings.

Why aren’t you in school? The answer is simple: girls don’t “need” education at least, that’s what many believe. A girl’s role is to care for the home, eventually find a husband, have children, cook, and maybe work as a maid or in a restaurant. So, there's no investment in her education. This mindset is often rooted in poverty. When money is scarce, education is prioritized for boys usually the firstborn. Girls are left behind, their futures determined by circumstances beyond their control.

In Kampala, the average rent for a modest home ranges from $30 to $550 per month. That morning, your oldest brother left at 7:00 a.m., carrying a roll of toilet paper for school, he’d been scolded the day before for not bringing his own. He also had to take a new broom to help clean the classroom and school grounds after lessons. School is expensive. Tuition alone is a challenge, but the hidden costs are even harder to manage. The school is six miles away, and each minibus ride costs about 50 pence. Then there are the extras no one talks about,yet everyone is expected to pay. Classrooms are overcrowded, often holding around 100 students.

To help your brother actually learn, your mother scraped together extra money to pay the teacher so he could sit at the front of the class,closer to the chalkboard, and where it’s easier to hear. She also paid for the teacher to check his homework, and if he needed extra help preparing for the P7 exam, there was a fee for tutoring too. That’s why only one of your brothers is in school. The others stay home, waiting and hoping that maybe an uncle or aunt might be able to help cover the cost of their education. That’s how it works for many families in Africa, parents often can’t do it alone. It takes the combined effort of the extended family just to give one child a shot at a better future.

Daughters often carry 5 gallon containers of water home for washing and laundry. One of your daily responsibilities is to care for the younger children. Laundry is done using two plastic tubs, with water you’ve hauled up a hill in that same 5 gallon container. But it’s not just washing, there’s cooking too. Meat isn’t something you worry about preparing, as there usually isn’t money for it, maybe just a few times a month. The shop is nearby, but you can’t request a specific cut; you get whatever is available, and the quality isn’t great. The meat is often tough, chewy, and exposed to flies, which poses a health risk. Live chickens are sold at the market, but they’re expensive,between $5 and $8, so they’re reserved for special occasions. If your brothers aren’t around, it’s your job to slaughter and pluck the chicken. The staple foods in Uganda are matoke (green bananas mashed and steamed in banana leaves) and maize flour, used to make a porridge or bread, like dish. Every evening, you buy a plastic bag of milk to drink immediately, since there’s no way to store it safely for later.

Every evening, you buy a plastic bag of milk for immediate use, as it would spoil if purchased earlier in the day. It’s sold by roadside vendors pushing carts, and if you're lucky to grab a bag from the bottom of the pile, it’s still relatively cool. Bread is also available from the same hawkers, who call out their goods as the sun sets, their wares lit by small oil lamps. In the mornings, it’s your job to go to the market to buy stalks of bananas and sweet potatoes,if there’s any money to spare. Red kidney beans are another option, but during the rainy seasons, they’re often infested with maggots,hardly an appealing source of protein. Rice is available too, though it’s expensive and needs to be carefully sorted for stones, which are unpleasant and dangerous to bite into. You prefer potatoes and use them when you’re able to buy some beef,but again, it always depends on how much money the family has.

The future doesn’t feel very bright. People often talk about things improving, but you haven’t seen the change. Malaria still visits you regularly, and there’s always the threat of dysentery and cholera. Now that you're growing into a young woman, there’s another danger one that people don’t talk about openly. Your uncle has been saying inappropriate things, suggesting you visit him so he can “teach you how to be a woman.” No, things are definitely not getting better.

You wish you could learn to read and write, but that may never happen. Few in your family ever did. In the slum where you live, there are only two visible paths out. One is education. The other is the one your aunt has taken selling herself to men with money in hopes that one of them might take her in. But that’s not the way your church teaches. Just up the path from your home, in a small slum church, you heard messages of holiness, right living, and faith in a God who gives hope and a future.

You’ve held onto hope. You’ve prayed hard. But so far, that brighter future hasn't come. Maybe God is just busy in other parts of the world. You enjoy going into town with your mother to Owino Market, where rows of secondhand clothes are spread out for sale, even if you rarely get anything new. It’s been a while since you last received a new skirt, and the one you have has faded; the detergent has long since stripped away its original brightness. (Omo may get the dirt out, but it takes the color with it.)

You reach down to scratch your feet and notice a few more jiggers have burrowed into your soles. It’s time to cut them out again. There’s no money for a doctor, but your mother did a good enough job last time with a knife. Fun, for you, means playing with the other children. Sometimes, you all head to the spot where the men gather to drink the home brewed alcohol prepared by some of the women.

There, you dance to the beat of drums with the other girls. You enjoy it,everyone joins in, while the older men sit and talk about yesterday, today, and the dream of a better tomorrow. They speak often of miracles, still hoping for one to lift them out of the slum. A new lottery had just come to Kampala, and your uncle had spent his entire $30 salary on tickets,only to win nothing. Some laughed, but you just felt sorry for him. Recently, you heard about something new. An organization had opened a small office on the edge of the slum, enrolling children into school programs with no fees. They were even offering uniforms, books, transportation and some food.

You heard something new,something that stirred a small spark of hope. An organization had set up a small office on the edge of the slum, enrolling street children into school without requiring any fees. They were offering school uniforms, books, transportation, and even some food. The cost, they said, would be covered by a family far away from Uganda. They called it sponsorship.

Maybe it was real. Maybe someone out there actually cared about children like you. Maybe there was more to life than struggle. Maybe, just maybe, there was a door opening to something brighter,a chance to hope. The truth is, you and I can help turn that hope into reality for children in Africa. You can go, as I and many others have, and serve directly. Or you can give, partnering with an organization that’s already on the ground, making a difference. Sponsoring a child through Save Sunshine Shelter Kids costs just $45 a monthbut the impact is priceless.

Donate to us and we achieve our goal

One child at a time.